Do You Do Full-Contact?" - Not Unless I Want to Maim or Kill You.

Nov 16, 2015

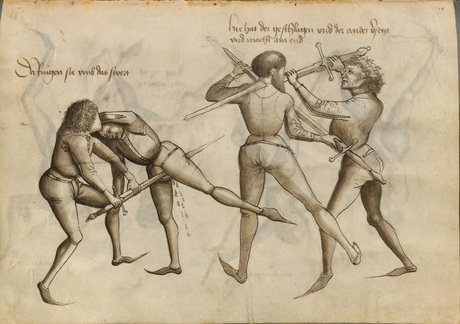

Talhoffer

I once had an interesting inquiry from a potential student who was looking for lessons in medieval swordsmanship. It began like this:

I’m interested in coming along. Just one question - do you do fencing or full-contact?”

A little perplexed, I replied: “I teach medieval fencing, we bout, but I’m not sure what you mean by ‘full-contact’.”

Within minutes, another message hit my inbox.

“Where you come away with bruises and shit.”

Wanting to find out more about this person’s particular - and perhaps peculiar - conception of what we actually do in HEMA, I asked: “Is that what you want to happen? You actually want to be injured?”

But instead of a reasoned explanation, the response was far more curious that I could have expected.

“I want to do full-contact, I want to get hit,” they stated. “Sounds like you just do fencing.”

Admittedly, I was baffled. I replied with the following.

“It’s inevitable that you will, occasionally, come away with bruises. That’s part of the risk. But what I teach is the art of defence with weapons. Even with blunt steel, it is simply too dangerous to use full intent in cuts and thrusts, particularly to the head.

“That said, everything we teach is directly from an historical manual and therefore potentially lethal if used in earnest with a weapon.

“The key to any martial art is control. You choose what force to apply and when to apply it. Anyone - and I mean anyone - can hit hard without any training whatsoever. It’s whether they can remain in control of themselves or their weapon when it matters which is important.

“The aim should always be to walk out as you came in.”

Consequently, I never heard from that person again. But it got me thinking - what is it with this notion of ‘full-contact’ that fixates some people? And why do they think that HEMA should accommodate it?

‘TRAIN AS YOU WOULD FIGHT’

I have to start at the beginning - what exactly is full-contact? In my mind there is only one answer. Full-contact is a fight. A straight-up, no-nonsense fight where stopping your opponent and self-preservation is the absolute priority. Take boxing, for example. Unless you are prepared to literally knock out your opponent, and vice-versa, then it’s training. And training must require an inherent respect for the well-being of one’s training partner. It shouldn’t matter whether it’s in the fencing school or the tournament ring. No one should be damaging anyone else, period … unless it’s a fight.

The reality is that we will almost certainly never fight another person in earnest with sharp swords …. unless we choose to visit some particularly colourful parts of the world to test out our skills. We are, at best, reconstructionists of historical combat. And there’s also the small fact when it comes to training in the Knightly arts - using those weapons common to the medieval professional soldier - we simply cannot and do not devote as much time as they did to try to become the warriors they were.

I use a modern analogy with my newer students. Imagine a six-year-old child who begins playing football daily and then joins a junior club. They train a few days a week, play a couple of matches as well. As they age and acquire the essential skills, they may progress to play in higher leagues. By their early teens, if they have special talent, they may be noticed by professional scouts. The best will go on to football academies and the most talented may get that dream signing for a professional club. The best of the best will go on to play for their country. By the age of 40, most of them will have ended their professional careers.

This is perhaps the closest modern equivalent to the development timeline of a professional Knight in the 15th century. Replace football with skill-at-arms, riding, archery, hawking, hunting, etiquette, the use of armour, tactics and mounted combat and, by their late teens or early 20s, you have a fully-rounded warrior elite.

The reality is that we can, at best, only attempt to understand part of this culture and we do so by poring over treatises and manuscripts before devoting a few hours a week to training a narrow band of fighting skills.

So how to we replicate what would otherwise be potentially lethal encounters, without breaking one-another?

I believe it makes sense to look at the military for direct context in what would constitute effective training for potentially lethal interpersonal combat.

As in medieval times, the modern soldier’s job is to fight and, if necessary, kill. They train for it, day in, week out. So how do modern soldiers train to fight? Are injuries common during phases of Close Quarter Combat instruction?

According to a 2012 report funded by the US Military Operational Medicine Research Program, almost six per cent of soldiers who took hand-to-hand combat courses at a Texas Army base were struck in the head and suffered symptoms the Pentagon said were consistent with concussions.

Troops must take at least 22 hours of the first level combatives course during basic training, with fighting techniques drawn from Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, boxing, wrestling and various martial arts. Researchers said their observations suggested that those soldiers undergoing the so-called Level One phase might be at the greatest risk for concussions, partly because of inexperience.

USMC MCMAP training

Col. Carl Castro, the director of the Military Operational Medicine Research Program, said the conclusions might dictate changes to improve safety. Castro also said there is no acceptable number of concussions for a training program, if there’s any way to avoid them.

“Even one per cent of soldiers would concern me,” he said. “I’d say we need to do something. We don’t want soldiers getting injured while training, if we can prevent it.”

A 2010 Order issued by the US Department of the Navy, laying out guidelines for the implementation of MCMAP (Marine Corps Martial Arts Program), further notes:

“There is a fine balance between exerting maximum effort and maintaining safe and effective exercise techniques. Instructors will ensure the emphasis on exerting maximum effort doesn’t predispose Marines to injury.”

So where does this relate to our practices within HEMA? There are a number of immediate differences, to begin with.

We are not soldiers who are expected to conduct real-life operations against a real enemy. The vast majority of military CQC which involves anything close to full-contact is unarmed. There is, of course, the use of the pugil-stick which involves protective headgear. Bayonet drills and marksmanship are not generally practiced against other human beings. A considerable section of HEMA training is conducted with weapons simulating sharp steel.

If we look for a comparison in HEMA, statistics provided for a major international tournament, staged in 2015 and involving 142 fencers, recorded that 18% of participants sustained some degree of personal injury. Eight people were restricted from competing after their accident, equating to approximately 5.3% of participants.

In the Open Longsword Tournament, 4.7% of participants sustained a ‘notable injury’, including a broken arm and fractured wrist. In total, 1.9% of all competitive participants required some sort of extended medical treatment.

Now this is not a criticism of those who organised that tournament, undoubtedly in good faith and with the intention to minimise risk as far as possible. However, it does concern me.

Yes, combat arts are risky - in fact, never mind combat arts, look at rugby! We know that there is an element of danger involved. And yes, accidents happen, but importantly we should also recognise the boundaries of what we can - and can’t - do in the HEMA ring. Just like high tackles, kicking, stamping and gouging are outlawed in rugby and deemed punishable offenses, there is also a line that must be drawn in HEMA.

Picture

‘FORCE MULTIPLIERS’

Bruising appears common among longsworders around the world, despite the attempts to mitigate injury by practitioners donning a wide array of protective gear. As well as improved fencing masks featuring back-of-head protection, the typical training bag contains gloves reinforced with kevlar plates, reinforced forearm bracers, heavy-duty jackets sometimes featuring rigid plates, elbow cups, knee cups and shin guards.

And this is the typical attire to allow us to simulate fencing without armour, as opposed to fighting in full harness.

Despite this ramping up of protective gear, particularly in tournaments, there are more serious injuries. Scalps have been split, noses bloodied, fingers broken and faces cut - not against unprotected targets, but actually through masks. Note that this isn’t only with heaver, longer weapons such as the longsword - sabres, messers, backswords, rapiers and even staves have all played a part.

It becomes clear that in such cases, unsharpened weapons are acting purely as force-multipliers. While a cut with a sharp sword will cause enormous trauma to an unarmoured target using only a moderate amount of force, excessive force with blunts has a propensity to cause injury even through the best modern HEMA protective equipment.

If the sword is reduced to a raw bludgeoning tool rather than a precision cutting or thrusting tool, combined with the ‘full-contact’ mindset, we have the inherently dangerous conditions of a fight rather than a training exercise or competitive bout wherein the risk of injury is most certainly increased beyond acceptable levels.

It is no longer the simulation of a fight with sharps under controlled conditions aimed at mitigating any real risk to both fencers.

Picture

THE ‘SAFE SWORD SIMULATOR’ FALLACY

From individuals, clubs and manufacturers, there is something akin to an ‘arms race’ to provide practitioners with valuable tools - and experiences to match - whether it be in practice weaponry, protective equipment or the explosion of digital resources to provide immediate access to primary source material.

Most notable has been the quest to create a cheap, durable alternative to the steel sword. While we prefer to use a rebated steel training sword at the HSD, the wider community has adopted a wide range of simulators - wood, modified shinai, nylon and, most recently, the historically-accurate Federschwert of the 16th century German Fechtschule being predominant.

But curiously, there has long been the notion that if it’s not made of steel, it’s somehow safer to hit harder with. I’ve actually heard the term ‘safe sword simulator’ being used to describe nylon wasters. This is a fallacy. Even if you replace nylon waster with wooden stick, it is still a fallacy.

As far back as the heady days of the mid-1990s, I remember being told that padded boffers - essentially a stick wrapped with pipe-lagging and duct tape - were far safer than steel because “you can really slam” with them.

Needless to say, concussions, severe bruising and even bone breaks have occurred with all of the above. And with the upsurge of the Federschwert being used to replicate longsword, the notion that it is somehow safer has again led to what I’d consider to be avoidable injuries from over-earnest use.

The answer, to me, seems to be relatively straightforward - it’s not the weapon simulator at fault, it’s the wielder. It doesn’t matter whether it’s wood, bamboo, nylon, rebated steel, a Federschwert or a table leg that’s being used. All of the above are far, far harder than the human body can tolerate, if used with high levels of force. Even through modern armour.

In short, none of the above are safe if put into the hands of an unsafe fencer. The real issue at stake is mindset and control - the use of appropriate force when necessary.

Why do I believe this? Because it’s what the historical masters tell us, over and over again.

“WITH THE ENTIRE BODY FENCE, WHATEVER YOU DESIRE TO EXECUTE STRONGLY”

Let us, for a moment, consider the above statement from Ms.3227a, compiled circa 1389. It is perhaps the keystone of why I believe some longsword fencers are locked in the mindset of ‘Strength Above All’. It’s often used to justify hard hitting.

Is the author telling us that we must strike strongly? Yes, he is. However, he’s also telling us that we must use the whole body - that fencing comes from the whole body, implying sound mechanics and footwork. But the most important aspect, for me at least, is the use of the word ‘desire’. This clearly tells me that I have a choice - if I desire to execute an action with strength, I can. Conversely, I can also choose to deny my desires.

Furthermore, Ms.3227a states:

“That is why Liechtenauer’s swordsmanship is a true art that the weaker wins more easily by use of his art than the stronger by using his strength. Otherwise what use would the art be?”

This is further evident as we are told to make use of both strong and weak in Liechtenauer’s system, to use one against the other - not merely strong alone. And we are given one of the Maisterhau - the Schielhau - which specifically addresses those who strike too hard and are disdainfully referred to as a ‘buffalo’.

“The Squinter (Schielhau) breaks into whatever a buffalo strikes or thrusts.”

“And this strike breaks all strikes of a Buffalo – which means peasant – that come downwards from above, as most peasants usually do.”

“Note here that the squinter is a cut which breaks-in the cuts and thrusts of the buffalo (one who acquires victory with power) …”

This disdain for ‘peasant’ strikes is not only confined to the German masters - in the Fior di Battaglia, written by Fiore de’i Liberi c.1409, we have the Colpo di Villano, which literally translates as ‘The Peasant’s Strike’. By entering with a weak bind in the middle of our sword against the Villano’s powerful sword blow, we let his momentum and lack of control bring his sword towards the ground, and we immediately respond with our own blow to the head or arms.

Crucially, Fiore also distinguishes between the reality of what is earnest combat and that done for training. Notably, he states:

“Also I, Fiore, told my students who had to fight in the barriers that fighting in the barriers is much and much less dangerous than fighting with cut and thrust swords in zuparello darmare (arming jacket) because to the one who plays with sharp swords, failing just one cover gives him death. While the one who fights in the barriers and is well armoured, can be given a lot of hits, but still he can win the battle. Also there is another fact: that rarely someone dies because he gets hit. Thus I can say that I would rather fight three times in the barriers than just once with sharp swords, as I said above.”

Even in the wrestling section of his Fior di Battaglia, Fiore also distinguishes that there are “holds of love and holds of war”, namely that there are some techniques that cannot safely be conducted in friendly circumstances.

The concept of finesse and ‘art’ overcoming brute force is again repeated in De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, written by the Pisan master Filippo Vadi c.1482. He notes: “Ingegno ogni possanza sforza” - “cunning wins any strength”.

Vadi also tells us to disregard courtesy when facing someone with “any hatred against you”. In contrast, that same courtesy should be extended to your opponent in friendly training which, in my book, includes bouting.

To my mind, there is a clear message in all of these examples:

- Use appropriate strength in appropriate circumstances.

- There is a distinction between what is permitted in bouting and in earnest combat.

- Bouting is not combat, but a preparation for combat or simply for exercise.

- Using too much strength is a base trait and to be avoided.

Brought forward into the context of modern HEMA, I would deduce the following from the advice of the historical masters:

- We are bouting, not fighting.

- As such, any notion of ‘full-contact’ violates the courtesy rule and, therefore, the social contract implicit in ‘friendly’ fencing.

- Where the above is ignored - i.e a bout is treated like a fight and force increases - injuries will occur.

CONCLUSION - WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

I’ve long felt that a serious debate has been needed within the HEMA community to address the question of force and its relation to what we’re actually trying to achieve. We’re all involved in reconstructing the art, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of running a gauntlet of injury each time we volunteer to cross swords with someone.

Yes, most of us can live with bruises and the odd knock. Coming away from a weekend with stitches in your head, mangled fingers or a broken bone is another thing.

If there’s one thing I hope this article achieves, it is to encourage HEMA practitioners to think before they act and to be clear in their minds of the potential consequences of their actions.

The notion of ‘full-contact’ with weapons should have no place other than in those dire circumstances when life and limb are truly on the line - not in the tournament ring when the only thing at stake is your ego or a medal.